Welcome - and thank you for your interest in Wind, the Heavenly Child!

Here you will find comprehensive insights into the topics of climate, CO₂, the environment, and energy—with a particular focus on wind energy. You will also find additional information about my book “Wind Mania— The wind mania and its climatic consequences”, which offers a critical examination of the effects of the current expansion of wind power on the climate and the environment.

What is wind?

Wind refers to moving air masses in the troposphere, the lowest layer of Earth’s atmosphere. In everyday life, we experience it as a light breeze or a powerful storm. When wind speeds reach around 118 km/h—force 12 on the Beaufort scale—they are classified as hurricane-force winds. Tropical cyclones such as hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones can be even stronger and possess enormous destructive power.

How is wind created?

The sun provides the energy that generates wind. When its rays strike water and land, they are converted into heat. At the water’s surface, however, a large portion of this energy is used for evaporation, which is why water warms up slowly. Dry land areas, by contrast, absorb the energy directly and heat up much more quickly.

These different heating processes create variations in temperature and, consequently, in air pressure between the areas over land and water. The air begins to move in order to balance out these differences—and this movement is what we call wind.

Note:

- About 70% of Earth’s surface is covered by water and 30% by land.

- In the tropics, solar radiation strikes strongly and directly, while near the poles it arrives at a weaker, slanted angle.

- Warm, moist air rises, cools as it gains altitude, and condenses to form clouds and precipitation.

- Regional contrasts in heating create local high- and low-pressure zones, and wind flows to balance these differences.

- The Earth’s rotation adds another effect: the Coriolis force, which deflects air movement to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere.

- Over the open sea, winds blow relatively undisturbed, but over land they are shaped by mountains, forests, and cities, features that channel the air into wind corridors.

- Air currents are especially strong along coastlines, where land and water meet. Winds also carry moisture from the oceans across continents, playing a crucial role in preventing drought.

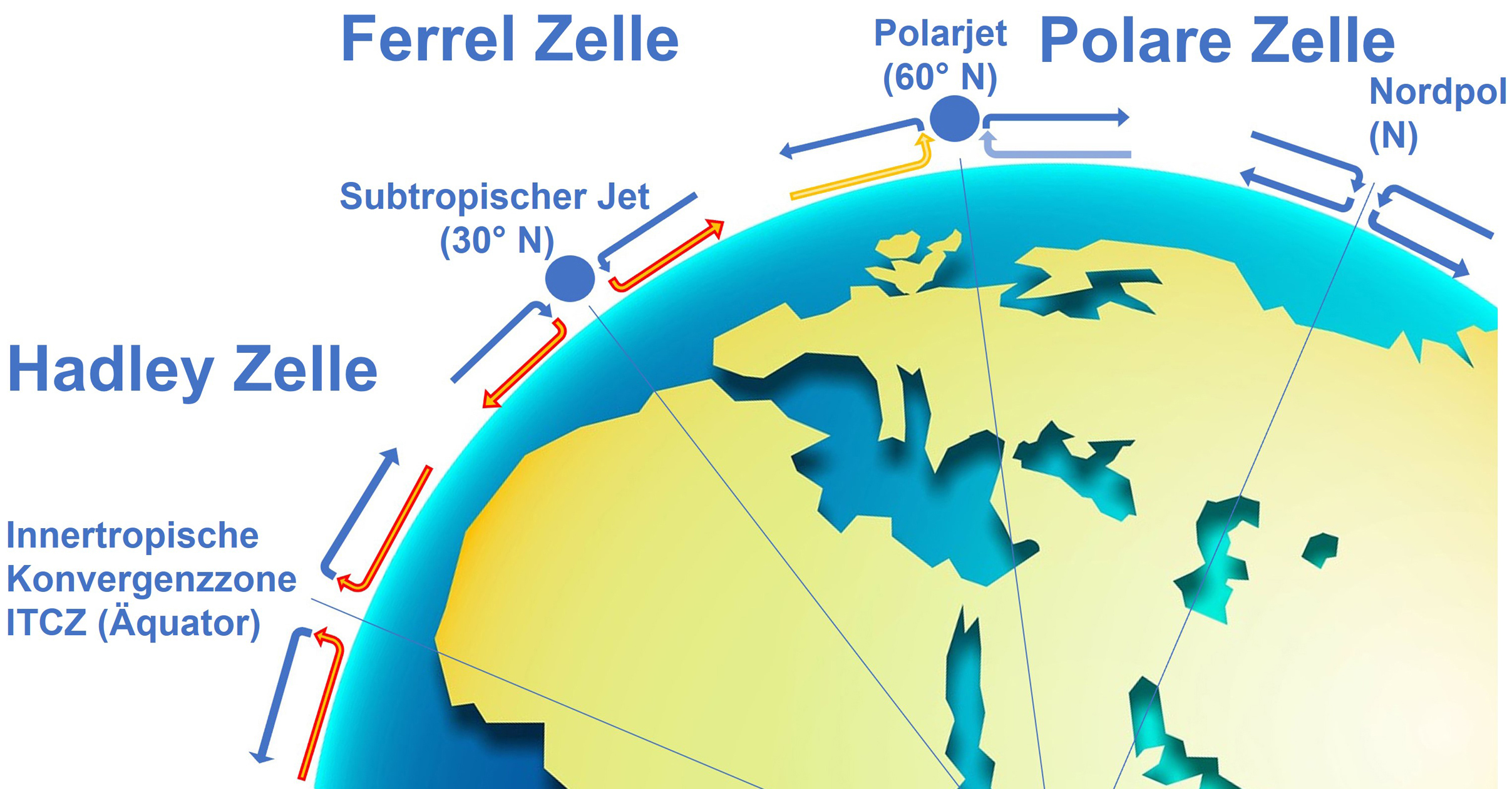

The Earth's rotation deflects atmospheric currents, creating distinct climate cells (see diagram). Polar cells are driven by cold downdrafts, while Hadley cells are powered by warm updrafts. In contrast, the Ferrel cell is indirectly driven, carried along by the neighboring cells.

Formation of climatic cells in the northern hemisphere

The global water cycle

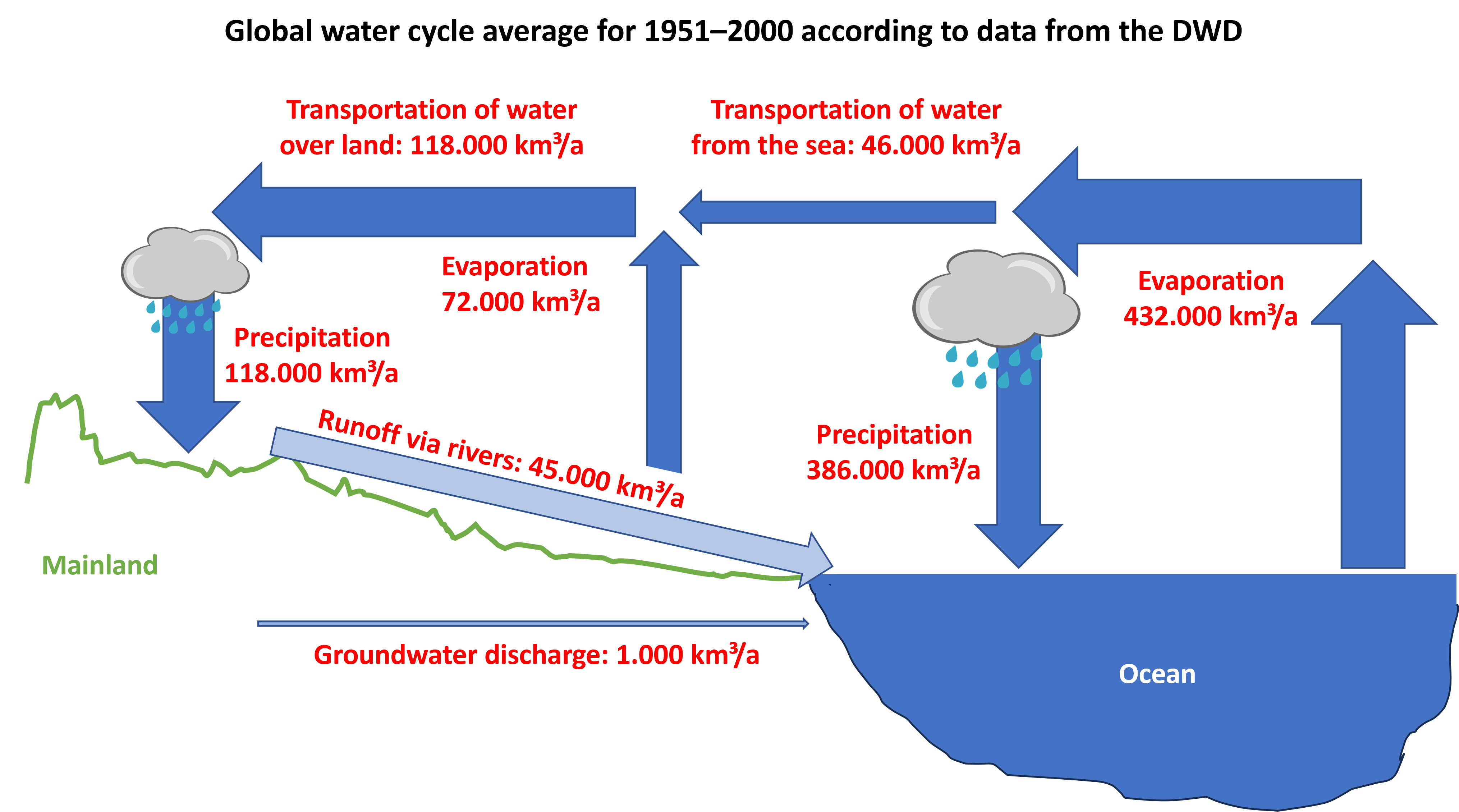

The global water cycle describes the continuous movement of water between the oceans, the atmosphere, and the land through evaporation, precipitation, and runoff. Because water easily changes its physical state, it rises as vapor, condenses into clouds, and returns to the surface as rain or snow.

Around 500,000 km³ of water evaporates each year. Of this amount, only 8–10% falls as precipitation over the continents. About one third of the rainfall over land originates from oceanic evaporation, while the remaining two thirds result from evaporation over the land itself. Almost all of the water that evaporates from the oceans eventually flows back into the sea through rivers.

Through the processes of evaporation and condensation, roughly one third of the solar energy that reaches Earth is transported back into space.

Differences in evaporation and precipitation result from the uneven distribution of land and sea, mountain barriers, and atmospheric circulation patterns. For instance, the Atlantic Ocean is considered a water-deficit region, while the Pacific Ocean shows a surplus due to its vast tropical waters.

Plants and oceans are the largest “evaporators.” However, large wind farms can disrupt the transport of water vapor from sea to land and its inland distribution, leading to regional drought and rising surface temperatures.

The sun and wind are the driving forces of this sensitive cycle, which has remained stable for millennia but is now being altered by large-scale human intervention in wind energy.

Wind energy use – a curse, not a blessing!

The term "renewable energy" suggests that energy can be replenished. In reality, energy cannot be renewed, only converted. A wind turbine extracts kinetic energy from the air and transforms it into electricity, which inevitably slows the wind. Even if wind occurs again the next day, this is not “renewed” energy but newly supplied energy.

This slowing reduces the reach of the wind and may influence the transport of moisture in the atmosphere - with potentially significant consequences for the global water cycle. It could contribute to regional imbalances, with some areas experiencing excess atmospheric moisture while others receive too little.

More on this ->

A common counterargument is that “a little less wind” makes no difference. This is misleading. Wind turbines are typically installed in areas with the strongest and most consistent flows, such as coastal regions or mountain corridors. As a result, energy extraction is not evenly distributed but concentrated in specific zones.

The scale of extraction is already substantial:

-

In Europe, wind power generated 428 TWh of electricity in 2023 and around 475 TWh in 2024. This corresponds to an average continuous output of 49 GW (2023) and 54 GW (2024)—roughly equivalent to 50 large power plants.

-

Globally, wind generation reached 2,304 TWh in 2023 and 2,494 TWh in 2024, equal to an average continuous output of 263 GW and 285 GW—comparable to around 250 large power plants.

However, installed output is only part of the picture. The crucial factor is the effect on atmospheric flows themselves. Assuming an average efficiency of around 30% in converting wind energy into electricity, the actual impact on air movement is roughly three times the generated power. This critical aspect is often overlooked in public debate, yet may already be reflected in observable changes in weather patterns.

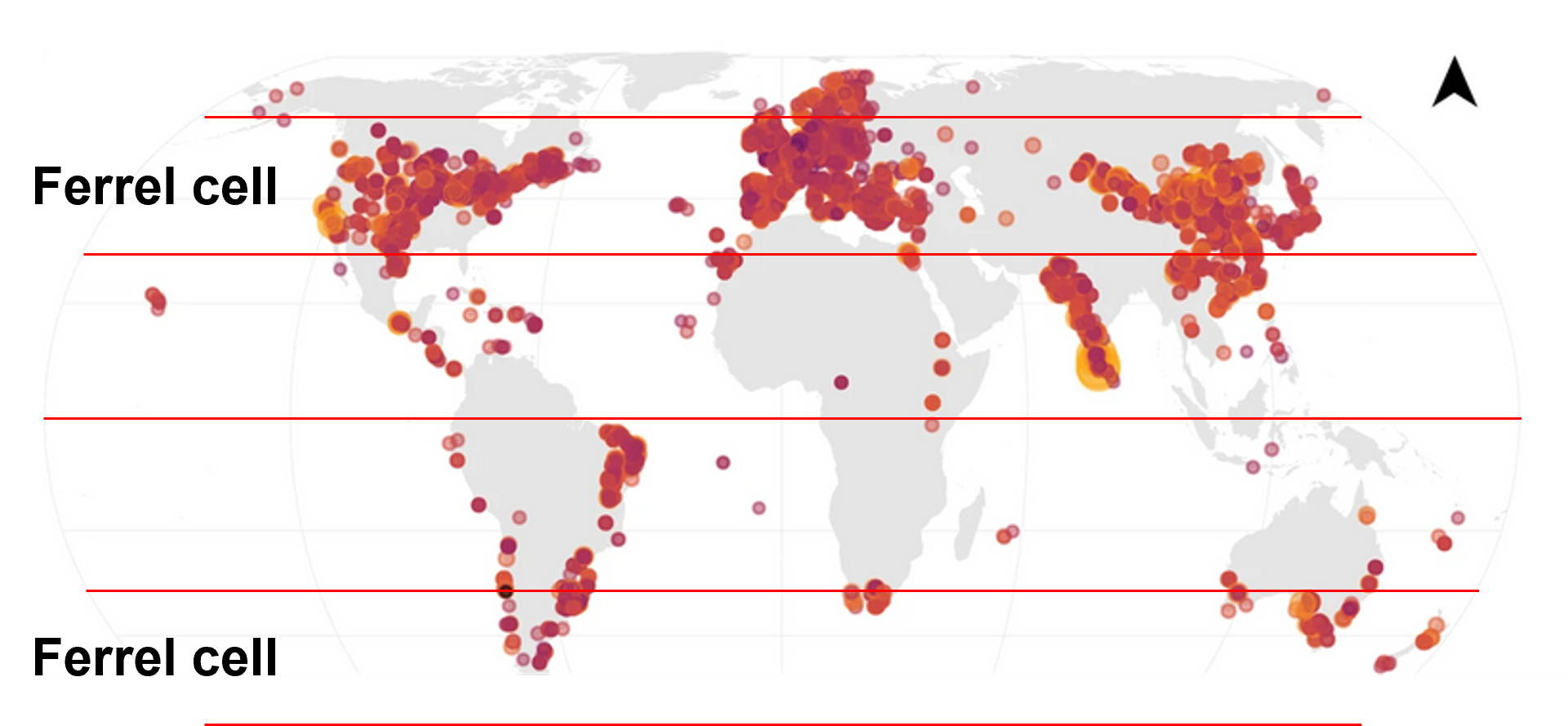

The graph (2020!) shows the accumulation of locations where energy is extracted from the tropospheric wind system (source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-020-0469-8

Europe lies mainly within this temperate Ferrel cell, where much of the wind’s energy is dissipated in both hemispheres.

This may help explain why Europe is warming faster than any other continent.

Further details on atmospheric structure, weather cells (Hadley, Ferrel, Polar), wind currents, and the global water cycle can be found in the book "Wind mania - The Wind mania and its climatic consequences".

Conclusion:

Wind is a central component of weather systems. Together with water vapor, it strongly influences the climate and drives the global water cycle. Wind balances temperature differences, enables the exchange of gases between water and air, and is therefore vital for both nature and humans.

Water vapor: an underestimated factor

The transport of water vapor by wind is often underestimated. Instead of stabilizing the climate, the global expansion of wind power may have the opposite effect: extracting energy from the atmosphere alters weather patterns, fosters drought, and heightens the risk of extreme events - effects that are already becoming visible.

DE

DE  EN

EN