Fusion Reactor: The Sun

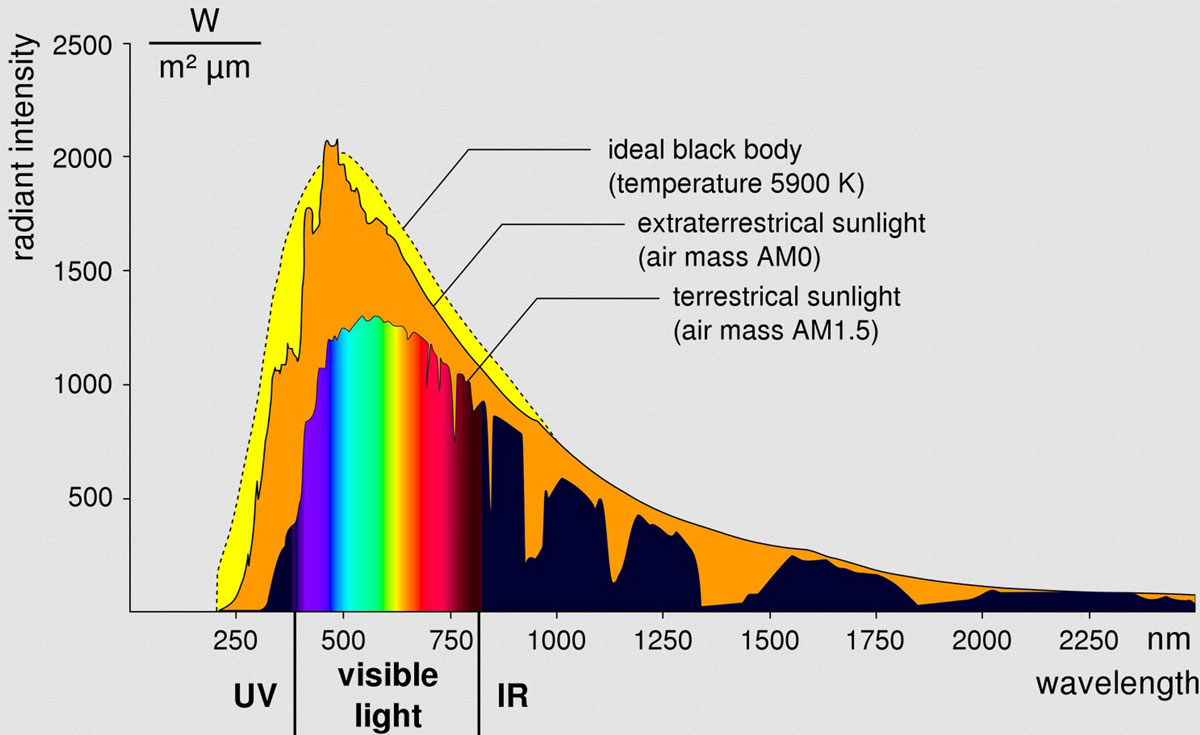

In the Sun, hydrogen continuously fuses into helium through a nuclear fusion reaction. The energy released in the process is emitted from the Sun in all directions into space as electromagnetic radiation traveling at the speed of light. The spectrum of solar radiation ranges from intense, short-wavelength X-rays to long-wavelength microwaves. Particularly relevant for us are UV radiation (100–380 nm), the visible range (380–780 nm), and infrared radiation (780–10,000 nm), which we perceive as heat.

(Wikipedia, (15.10.2023), https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonnenstrahlung)

How high is the Sun’s radiant power?

The Sun’s radiant power at its surface is around 63,000 kW/m². At the outer edge of Earth’s atmosphere, this results in an average irradiance of about 1,365 W/m² (incident perpendicular to the surface; defined in 1982 as the solar constant E₀). In reality, however, solar irradiance fluctuates due to Earth’s elliptical orbit around the Sun, ranging from 1,322 W/m² to 1,414 W/m².

Of the solar radiation reaching Earth across different wavelengths, about 19% is absorbed by the atmosphere and clouds. Around 26% is reflected within the atmosphere and 4% is reflected by Earth’s surface back into space (albedo). Approximately 51% of the incoming solar radiation is used for photosynthesis or is absorbed by Earth’s surface, objects on it, and bodies of water, where it is converted into heat.

How do the Sun’s rays affect the atmosphere?

In addition to reflection and absorption by particles, clouds, and water vapor in the atmosphere, the scattering of incoming sunlight has a particularly significant influence on the illumination of Earth’s surface and, above all, on the color of the sky.

As light is scattered by atmospheric gases, it is distributed throughout the entire atmosphere (Rayleigh scattering), filling the air with light and brightening it through diffuse shortwave radiation in the blue range—resulting in the blue sky.

Without this diffuse scattering, when looking into space we would otherwise see only a black void with a bright white Sun. Increasing turbidity of the atmosphere—for example due to water vapor, dust, or aerosols—enhances scattering in favor of long-wavelength radiation, causing the sky to become hazier and appear gray (e.g., smog).

Red sunsets and sunrises are based on the same physical principles: long-wavelength red light is scattered much less and can still be seen when the Sun is low on the horizon, whereas the shorter-wavelength blue light is scattered more strongly and is therefore deflected (filtered out).

The Earth is not a greenhouse!

It can therefore be concluded that we do not live under a dome. The “sky” is primarily an optical phenomenon and cannot retain energy in the form of thermal radiation—regardless of wavelength or direction—like a solid enclosure (e.g., the sharp temperature drop on clear nights).

Heated matter releases energy in essentially the same way it was absorbed: through the emission of electromagnetic radiation. Overall, the Earth emits roughly the same amount of energy into space each day as it receives from incoming solar radiation. If this were not the case, the Earth would warm continuously and very rapidly, since the amounts of energy involved are enormous—as will be shown below.

The latent heat in the atmosphere is stored mainly in water vapor.

How much energy from the Sun is radiated onto the Earth per hour?

Due to the Earth’s spherical shape, its surface is not illuminated evenly everywhere. The highest solar irradiance occurs near the equator, while the lowest occurs at the poles. Under the common assumption that 30% of the incoming solar radiation is reflected directly back into space (albedo), only about 956 W/m² remains available for warming.

To calculate the total incoming energy, the effective area is taken as the cross-sectional area of the Earth, i.e., the area of a circular disk with the Earth’s diameter. However, the Earth’s actual surface area is about four times larger. For this reason, the average solar irradiance of 956 W/m² is divided by a factor of 4, resulting in a theoretical mean incoming irradiance of approximately Pe = 240 W/m².

The Earth’s surface area Ae is 5.067 × 10¹⁴ m². Multiplying this area Ae by Pe = 240 W/m² results in an incoming power of 1.216 × 1017W. Over the course of one year (8,760 h), the total energy input is therefore: 1.216 × 1017 W × 8,760 h = 1.065 × 1021 Wh, or 3.835 × 1024 Ws = 3.835 × 106 exajoules.

Per hour, the average energy input from the Sun to the Earth is thus: 3.835 × 106 / 8,760 h ≈ 438 exajoules.

For comparison:

The amount of energy reaching the Earth’s surface per hour through solar radiation corresponds to about 68% of the world’s annual primary energy consumption, which is just under 650 exajoules (2024). The additional energy input into the atmosphere caused by all of humanity is therefore marginal in comparison.

In summary, it can be stated that it almost seems like a miracle that the Earth’s surface and the troposphere do not continuously heat up despite the enormous daily exchange of energy, but also do not cool down excessively. These figures also clearly illustrate how small the influence of humans on the climate realistically is, and how limited the active impact of humanity as a whole can be.

What percentage of incoming solar energy is converted into wind?

Only about 1–2% of the solar energy received globally is converted into the kinetic energy of moving air masses. A large portion of this energy remains in vertical convection or is dissipated through waves and friction. Globally, only 0.5–1% remains available for horizontal wind flows.

And it is precisely this comparatively small share that is being tapped through the use of wind energy. The resulting climatic impacts are already visible—but are being ignored for ideological reasons.

Further and more detailed information on the issue of extracting energy from the tropospheric system, its effects on wind circulation, and the global water cycle can be found in the book:

Windwahn - Der Windwahn und seine klimatischen Konsequenzen.

DE

DE  EN

EN